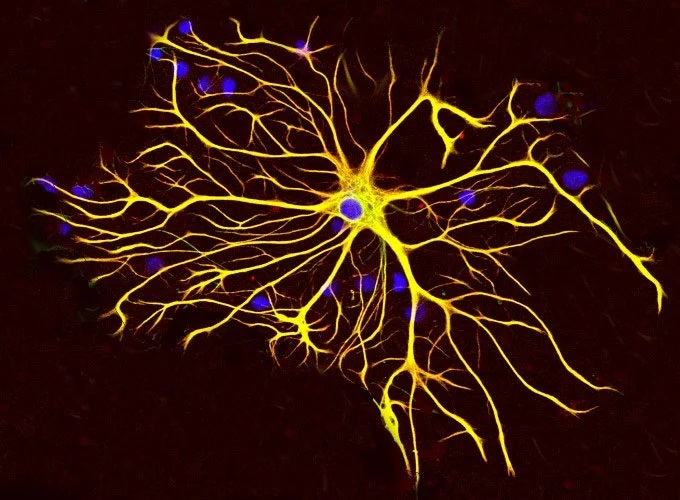

People with depression have a distinctive feature in their brains that have fewer astrocytes, a type of astrocytes, than the brains of normal people, according to a new study.

Study co-author Liam O’Leary (Department of Psychiatry, McGill University in Montreal) told Live Science: “Astrocytes are greatly affected by depression.

This has been known for some time, but this finding shows that it occurs throughout the brain and not just in a specific region of the brain. This leads us to believe that the decrease in the number of astrocytes plays a more important role in depression, which could influence new treatment strategies.

The study, published Feb. 4 in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry, joins a team of researchers showing that astrocytes may play a role in depression. The authors say that the development of drugs that increase the number of astrocytes or support the functions of astrocytes could represent a new avenue for the treatment of depression.

“The good news is that unlike neurons, the adult brain is constantly producing new astrocytes,” study lead author Naguib Mechawar, professor in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, said in a statement.

To confirm that these changes associated with depression affected astrocytes throughout the brain and not just those containing GFAP, O’Leary and his colleagues looked for another astrocytic marker, vimentin, present in the brains of depressed individuals and not depressed.

The researchers labeled two astrocyte marker proteins, GFAP and vimentin, in the postmortem brains of 10 people with depression and 10 without psychosis who died suddenly from causes unrelated to mental health.

The researchers looked at three different brain regions – the prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and caudate nucleus – that are believed to be involved in regulating emotions, O’Leary said. Overall, the density of astrocytes in the brains of people with postmortem depression was lower than that of people without depression.

Understanding the link between reduced astrocyte density and depression will require more research, says O’Leary. For example, it is not known whether depressed people lose astrocytes over time or have fewer astrocytes to start with.

He added, “With the tissue from the autopsy, we can only see a snapshot of the anatomy. So the real functional explanation has to come from animal studies, which might help to test something and understand the difference. “

The reduction of astrocytes in the brain regions studied here could have a negative effect because these brain regions form a circuit considered important for decision-making and emotional regulation. With fewer astrocytes to support them, the neurons in this circuit may not function as well as they should.

Researchers hope that new knowledge about the link between astrocytes and depression could lead to new treatments.